Bloody Stools Link aHUS and Inflammatory Bowel Disease in 3 Boys Detailed in Case Study

Bloody stools in children with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) may indicate the simultaneous presence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), three case studies report.

These findings raise questions about the connection between aHUS and its associated defects in the complement system, and the gut inflammation characteristic of IBD.

The cases were reported in the study “Comorbidity of inflammatory bowel disease with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in pediatric patients,” published in the journal Clinical Nephrology Case Studies.

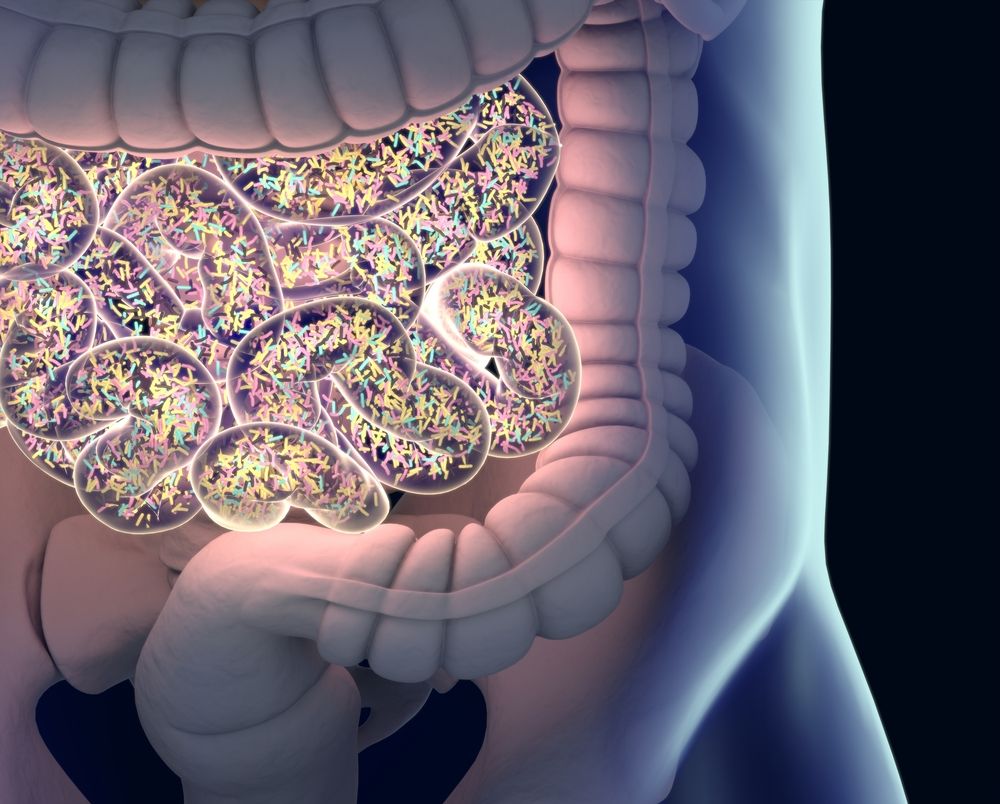

aHUS is an extremely rare disease characterized by the destruction of red blood cells (hemolytic anemia), low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia), and organ failure, most commonly acute kidney failure.

Most cases of aHUS are genetic, although some may be acquired due to autoantibodies or occur for unknown reasons. The disease’s root cause is an excess activation or malfunction of the alternative complement pathway, a part of our innate immunity (known as our first line of defense).

In about 50% to 80% of children with aHUS, these defects are triggered by an infection, most commonly a lung or a gut infection, but other processes may be involved.

The association between IBD and aHUS is poorly described. Only six cases are reported in the literature, and nearly all are in adults.

Here, researchers detail the cases of three boys, ages 13, 12 and 11, who were diagnosed both with aHUS and ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, two types of IBD.

The oldest had ulcerative colitis and was admitted to the emergency room after one week of abdominal pain, vomiting, and worsening blood in stool (hematochezia).

He was seen to have significant anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute kidney injury, all hallmarks of aHUS. Several workups and genetic tests pointed to an aHUS diagnosis, but not one of genetic origin.

He was treated with eculizumab (sold as Soliris, by Alexion) over 38 weeks, and since his blood values have remained normal and his kidney function has improved. Ulcerative colitis also remains under control with mercaptopurine.

For the other two patients, detection of aHUS came before IBD diagnosis.

According to researchers, this suggests a link between complement malfunctioning and subsequent gut damage, possibly because the first causes blood clots in small gut vessels (thrombotic microangiopathy) that eventually lead to IBD.

One of the boys entered the emergency room with fever, abdominal pain, and acute onset of cola-colored urine. Lab testing revealed typical signs of aHUS — anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute kidney injury.

He was initially treated with plasma exchange, which worked to normalize his condition. However, the disease came back 15 months later, requiring hemodialysis. Subsequent genetic testing revealed a mutation in the MCP/CD46 gene, consistent with aHUS.

Two years later, the patient developed bloody diarrhea and showed weight loss, confirmed by upper endoscopy and colonoscopy to be caused by Crohn’s disease.

The third boy had a known history of aHUS, controlled with plasma therapy and eculizumab, when a disease relapse accompanied an infection.

Following one year of treatment with eculizumab, anemia came back and he also started having diarrhea, with stools positive for occult blood.

Further exams revealed signs matching Crohn’s disease. He has now been on a combination of eculizumab, mesalamine, and infliximab (brand names Inflectra, Remicade, Renflexis, and Ixifi, among others) with clinical improvement and no evidence of aHUS recurrence.

These three cases highlight a possible interplay between aHUS and IBD. On one side, changes in complement function present in IBD patients could contribute to activation or reactivation of aHUS.

On the other, aHUS may lead to gut inflammation and IBD. Disruption of small blood vessels (microangiopathy) caused by aHUS could disturb gastrointestinal mucosa and lead to bacteria leakage and inflammation promoting IBD.

This could explain the two cases in this series where a diagnosis of aHUS preceded the diagnosis of IBD. Consistent with this idea, “it is interesting to note that with adequate suppression of the complement system [eculizumab] in one of the 3 patients reported here, the clinical symptoms of IBD improved markedly,” the researchers said.

However, this link is still speculative and further research is needed to better understand it, they stressed.