Anti-VEGF medications likely triggered aHUS in man, 44, per case report

These drugs often are used to treat diseases that cause vision problems

Written by |

Intensive treatment with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) medications — commonly used to treat disorders causing vision impairments — are thought to have led to the onset of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) in a man in his 40s.

It is a rare finding in an extremely rare disease, according to a new report.

“To the best of our knowledge, only two case reports have previously described the association of … anti-VEGF [medications] with aHUS,” the researchers wrote.

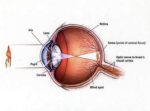

This case highlights the “limited understanding of the ocular [eye-related] signs of aHUS,” the team noted, adding that “ophthalmologists should be aware of the ocular manifestations of the disease because they can be the leading sign of the disease.”

The man’s case was described in a letter to the editor, titled “Ophthalmic manifestations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome triggered by intravitreal anti-VEGF,” published in the Journal Français d’Ophtalmologie.

Patient received long-term treatment with anti-VEGF medications

In aHUS, a part of the immune system called the complement cascade is overactive, leading to inflammation and blood clotting in small blood vessels. Called thrombotic microangiopathy, it can damage internal organs, particularly the kidneys. Despite being rare, eye involvement also has been reported in aHUS.

Most people with aHUS have mutations in genes that regulate the function of the complement cascade. Mutations in the genes CFHR5 or MCP can increase a person’s susceptibility toward developing the condition.

aHUS also can be triggered by certain therapies, such as anti-VEGF medications, which are widely used for the treatment of conditions affecting the retina — a region at the back of the eye that contains cells that sense light and nerve cells that transmit visual signals to the brain, enabling a person to see.

Now, researchers in Spain reported the case of a patient who developed aHUS after receiving long-term treatment with anti-VEGF medications.

The 44-year-old man had progressive loss of visual acuity in his right eye, but no history of previous diseases. An eye exam revealed macular edema — fluid accumulation within the retina that causes swelling and potential visual problems — and tortuous or twisted small blood vessels that were leaky.

The man initially was diagnosed with venous stasis retinopathy, a condition that occurs when veins in the retina become blocked, making it difficult for blood to flow out of the eye.

For his macular edema, he received injections of two anti-VEGF medications for several months. In total, he was given 13 injections of ranibizumab (sold under the brand name Lucentis among others) and nine injections of aflibercept (sold under the brand names Eylea, among others).

However, no improvements were seen.

Condition also affected patient’s other eye after 2 years

Two years later, the condition began to affect his left eye, for which he again received anti-VEGF injections.

However, an eye examination revealed signs of Purtscher-like retinopathy, a rare disorder that affects the retina and is possibly linked to chronic kidney disease. Further blood work seemed to confirm such a finding.

The patient was referred to the nephrology department and was diagnosed with acute kidney failure accompanied by high blood pressure. Additional tests suggested microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, or red blood cell destruction occurring within small blood vessels.

He was hospitalized and treated with intravenous or into-the-vein methylprednisolone, a glucocorticoid.

Genetic tests revealed the presence of variants in the MCP and CFHR5 genes, and a kidney biopsy came back consistent with thrombotic microangiopathy. These findings led to a diagnosis of aHUS.

Anti-VEGF injections were halted due to the suspicion that they might have caused the patient’s kidney impairments. His kidney function declined rapidly and he started hemodialysis, plasma exchange, and pharmacological treatment with a complement inhibitor targeting a complement protein called C5.

He was discharged, but during follow-up he voluntarily withdrew from treatment with C5 inhibitors. A month later, he again showed signs of eye involvement, namely blood accumulation and high blood pressure in his right eye, which failed to ease with treatment.

The patient underwent eye surgery. However, following the procedure and during an hemodialysis session, he had a tonic-clonic seizure. A brain MRI revealed signs of hemorrhages, or bleeding, which were attributed to aHUS.

He was placed once again on complement C5 inhibitors, which successfully suppressed complement activation. Despite this, his general condition worsened and the patient died. An autopsy confirmed the presence of thrombotic microangiopathy in his main vital organs.

Overall, “in this genetically predisposed patient, treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents triggered renal and systemic [whole-body] microangiopathy,” the researchers concluded.