Rare Disease Groups Welcome FDA’s Embrace of ‘Real World’ Data in Clinical Trials

Written by |

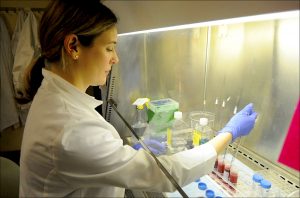

Kate Stringaris, a researcher with the NIH’s National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, separates lymphocytes from a blood sample as part of an investigation into natural killer immune cells.

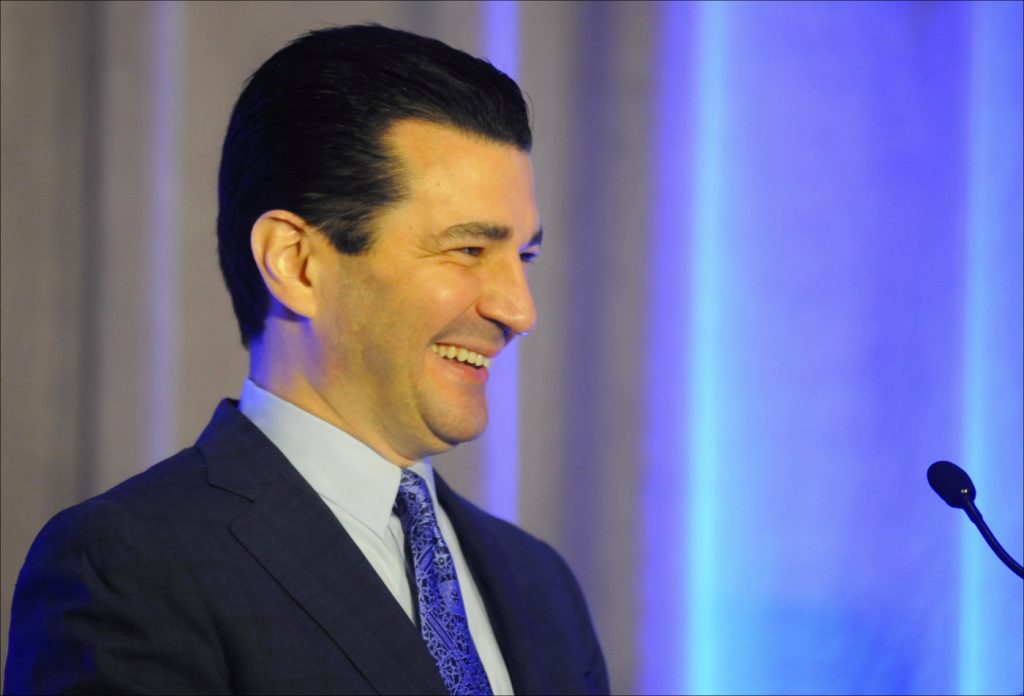

In his 10 months on the job, Commissioner Scott Gottlieb of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is earning praise for his efforts to make clinical trials for new therapies more flexible and responsive to the needs of rare disease patients.

From cystic fibrosis to epidermolysis bullosa, the FDA — with Gottlieb, a physician, at the helm — appears increasingly willing to engage patient advocacy groups in designing trials that incorporate more meaningful endpoints and “real-world” data, as well as natural disease histories. It’s an effort to move beyond the traditional, randomized, and placebo-controlled trials that began before him, but which Gottlieb and the agency embrace.

“The result has been faster reviews of drug applications by FDA, greater success by drug sponsors in getting FDA approval, and a process that gets new drugs to American patients faster than anywhere else in the world,” William K. Hubbard, a former FDA official, now a North Carolina-based pharmaceutical industry consultant, said in an interview with Bionews Services.

During his 30-year career with the federal agency, Hubbard said, the trend was toward increasingly efficient clinical trials and coordination with industry in designing them.

“Commissioner Gottlieb can be expected to continue, and even accelerate, those improvements by such mechanisms as greater use of adaptive clinical trials and surrogate endpoints,” Hubbard stated in an email. “The key will be to make those changes without compromising the ultimate goal of assuring safety.”

A case in point is the FDA’s unprecedented approval of the event rate of pulmonary exacerbations — rather than the long-accepted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), a standard measure of lung function — as a decisive measure (called a primary endpoint) in a Phase 2b trial testing lenabasum as a therapy for cystic fibrosis.

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF), which recently awarded Corbus Pharmaceuticals a $25 million research grant to develop lenabasum and supported the FDA’s January 2018 decision, said it “makes sense that an anti-inflammatory treatment would have an impact on pulmonary exacerbations and an individual’s rate of decline in FEV1 over time, rather than just causing an acute change” in FEV1.

“We believe the FDA’s decision to move forward with this endpoint provides a path forward for this and other anti-inflammatory drug candidates, which are desperately needed by people with cystic fibrosis,” said a CFF spokesperson who asked not to be named — adding that the Bethesda, Maryland-based nonprofit supports the agency’s approach to clinical trials in general.

“Given the rapid advance of CF therapies, it may be difficult in the future to perform certain trials with long placebo periods,” the spokesperson said. “The CF Foundation has discussed this on several occasions with the FDA, and we are grateful that they are open to new strategies.”

Natural history studies advance

One such strategy is the use of natural history models to reduce the need for placebo arms in studies of therapies targeting very rare conditions. The FDA defines the natural history of a disease as the course an illness takes from its onset, through the presymptomatic and clinical stages, to a final outcome in the absence of a treatment.

The agency agreed to fund four such natural history studies in October. The grants, which total $6.3 million over the next five years, will go to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for Friedreich’s ataxia ($2 million); New York’s Columbia University Medical Center for pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis ($2 million); the University of Iowa for sarcoidosis ($300,000); and the University of North Carolina for sickle-cell anemia ($2 million).

Through a partnership with the National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the FDA will also give $2 million each to Boston Children’s Hospital to study Angelman syndrome, and the University of Utah to study myotonic muscular dystrophy type 1.

“We’ve been working overtime to develop models that can simulate the behavior of placebo arms in the setting of rare diseases, where recruiting for clinical trials can be especially hard,” Gottlieb said in an FDA press release announcing the grants.

Three months ago, the National Network for Excellence in Neuroscience Clinical Trials (NeuroNEXT) — with funding from the NIH — published a two-year study, “Natural history of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy.” The trial, led by Ohio State University, involved researchers at 15 NeuroNEXT sites. Data collected were used to bolster Biogen‘s application to the FDA to approve Spinraza (nusinersen), the first disease-modifying treatment for spinal muscular atrophy.

FDA approvals for Batten, Duchenne therapies

Margie Frazier, executive director of the Batten Disease Support & Research Association, warmly welcomed the FDA’s approval of Brineura (cerliponase alfa) in April 2017. The BioMarin therapy, which is injected directly into cerebral brain fluid, costs $702,000 a year and helps Batten children with the CLN2 genetic mutation.

“Certainly in our experience with enzyme replacement therapy, the natural history data was absolutely key to that approval,” Frazier said in an interview. “It was compelling in that it shows an immediate dropoff in children’s health between the ages of 3 and 5. This data may not have been used in larger trials or double-blind trials, and we could have missed out on a treatment.”

She added: “We were glad that our partners working with us on registries over the years were able provide the right information for BioMarin and the FDA to come to a resolution on approval … We’re seeing kids benefit from it every day.”

Yet when it comes to the endpoints, or specific objectives, of clinical trials, Frazier said there’s room for improvement.

“We talk about things like 6-minute walk tests and verbal ability, and the ability to dress oneself. All these are ways of measuring children’s health and mobility, but they’re not always correlated with what’s important to parents, and what’s important in the day-to-day qualify of life of these kids who have very debilitating rare diseases,” she said.

“I think we have to get much better at systematic study of those things as endpoints as well.”

Registries, real-world evidence support ‘revolution’

Given the very small patient populations associated with rare diseases, extra flexibility must be built into clinical trials assessing therapies to treat them, says Paul Melmeyer, director of federal policy at the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD) in Washington.

“More and more,” he said, “pharmaceutical companies and the FDA are embracing patient-focused endpoints, inclusion criteria, and other aspects of clinical trials so that the therapies actually coming to market are more reflective of what those patient populations actually desire.

“We’re still very much in the inception of this revolution, in a sense,” added Melmeyer, whose organization is an umbrella group of 270 patient advocacy groups. “There have not been any therapies approved based on quality-of-life indicators, but there have been ones in which reviews have been substantially influenced by patients and feedback. We’re also talking about the inclusion of patient preference information, patient experience data, and real-world evidence reported by patients.”

NORD has created about 30 registries in coordination with its patient organizations, which collects data from the rare disease communities they represent.

Jennifer Miller, an assistant professor and clinical trials transparency expert at New York University School of Medicine, said such real-world evidence is crucial. That’s because the results of clinical trials, with their specialized populations and situations, do not necessarily apply to all.

“A lot of these trials are highly controlled, and participants tend to be healthier, younger and whiter than the average patient,” she said, adding that trials involving placebo arms are based on regulations originally designed to protect patients.

“But now the world looks very different, and the way we generate and analyze medical evidence is changing,” she said. “There’s a lot more data, and with more data comes better data, such as wearable devices as well as more patient-centered outcomes. We’re looking at engaging patients and seeing what outcomes they want and need to see from medicine, which is a shift away from a more paternalistic model.

“In general, we’re trying to democratize our data to make sure clinical trial evidence responds to the needs of as many patients as possible.”

Brett Kopelan, executive director of debra, a New York-based nonprofit group for people with epidermolysis bullosa — a rare inherited connective tissue disorder — said Gottlieb’s push to use real-world data rather than relying only on placebo-controlled trials makes sense.

“Natural history about a disease clearly shows what current treatments’ efficacies are, so comparing that to a new drug or therapy is quite frankly more efficient,” said Kopelan, a former NORD board chairman. “If you have studied the natural history of a disease and you know how it progresses, why not use that data when looking at the potential efficacy of a therapy? Why ignore it?”